Dropwise condensation modeling in python

As part of my PhD research, I wanted to find out how the various parameters of dropwise condensation influence the heat transfer. So I took one of the available thermodynamic models, my rudimentary python skills and started plotting some graphs. The result was surprisingly useful and helped me to get a feeling for the different parameters that influence dropwise condensation. Later, when I took part in an open science mooc at my university, I decided to share the code. Here’s what I have learned along the way.

What is it about?

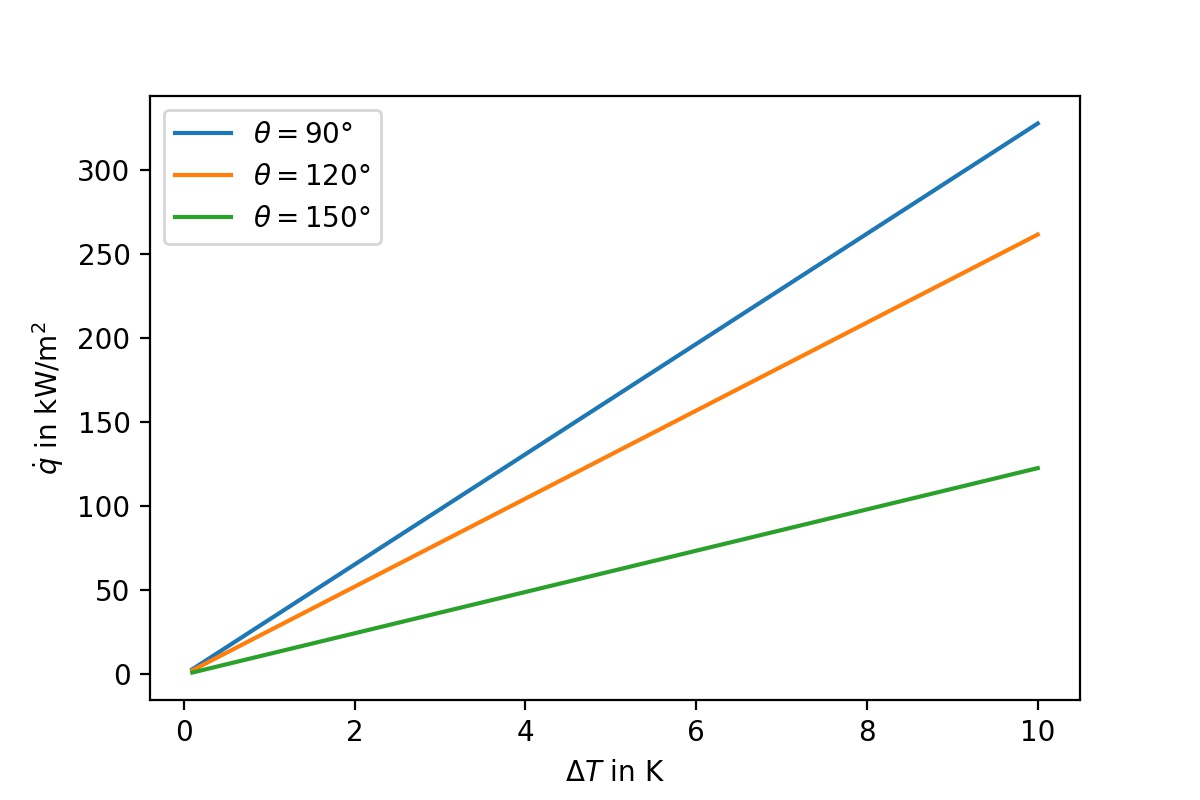

The idea of my python script was, to quickly generate graphs which show how certain parameters (like contact angle, surface subcooling temperature and fluid properties) influence dropwise condensation. For example, what impact does the contact angle have on the heat flux? The following graph shows, that the heat flux is actually decreasing when the contact angles get very large:

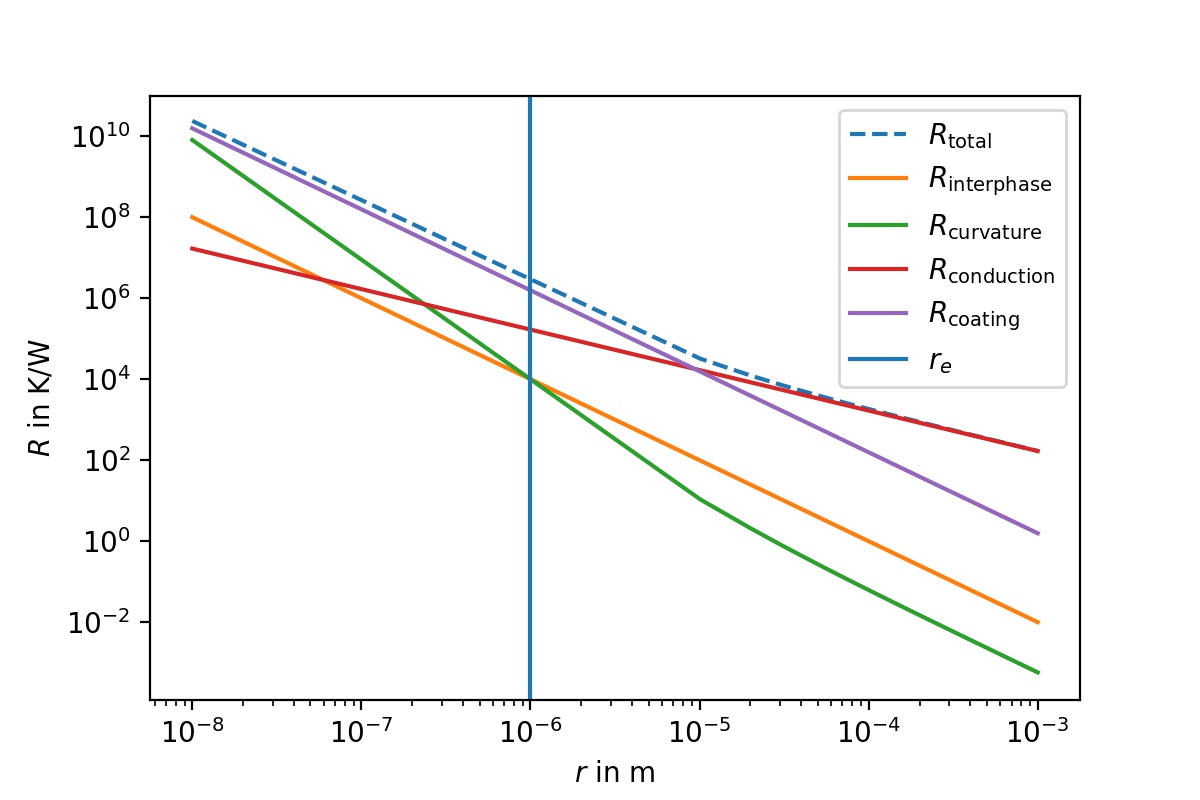

Also very interesting: which thermal resistances are dominant in a single droplet?

These kind of parameter sweeps worked great and I gained some new insights from the graphs. For example: in most cases, the interfacial heat transfer coeffient has only a minor influence on the overall heat flux. Thus, experimental investigation of this parameter should not be my top priority.

But now I wanted to share my code and make the graphs reproducible for everyone…

Using the right tools

GitHub is the go-to platform for managing open source software development. It is also great for sharing research related code like my little python script. And of course, it helps with version management as well… In regard of open science and reproducible research, the real power of GitHub comes from its integration in other services. Two of them are especially interesting:

Zenodo.org provides DOIs for GitHub repositories, making your code citeable. Even better: a new DOI is generated automatically for each version that is released via GitHub. This way, older versions of the code are still accessible and all of the DOIs are related to the version history of the code on zenodo.org.

Another great tool for open science is binder. I am using jupyter notebooks to run my python scripts and with binder, these notebooks can be built directly from a GitHub repository in your browser. The necessary environment is built automatically and there is no need to download any packages (or having python installed at all). This means, anyone can run the code and interact with it, pretty much regardless of the system they are using. It even works on mobile devices.

Finally…

Once I had figured out how I could share the script, I had some second thoughts: Should I really publish such an unpolished, hacked-together code? What if there are errors in my implementation of the model? These questions are probably not uncommon amongst researchers without a strong programming background. The thing that finally convinced me to upload the code was this old nature column, which addressed most of my concerns. So here are the results:

- the GitHub repository of the script

- the corresponding zenodo page

- and here, you can run the code in your browser and plot your own graphs

At this point, I don’t know if I will keep working on the script. Many things come to mind that could be improved and added, but currently, my focus lies elsewhere. However, if someone else finds the script to be helpful, it can be used freely under the MIT license.

For me, it was really interesting to see how these different tools can be used together. Especially the combination of jupyter notebooks and binder seems great for open and reproducible research. For those who want to learn more about using GitHub in a research context, I recommend the following introductional online course: Open Research Software and Open Source (it’s free).

Acknowledgements

This is the original paper on the thermodynamic model that is implemented in the script:

Kim S, Kim KJ. Dropwise Condensation Modeling Suitable for Superhydrophobic Surfaces. ASME. J. Heat Transfer. 2011;133(8):081502-081502-8. doi:10.1115/1.4003742.

All fluid properties required for the model are calculated with the great CoolProp library.